Author: Jonathan Williams

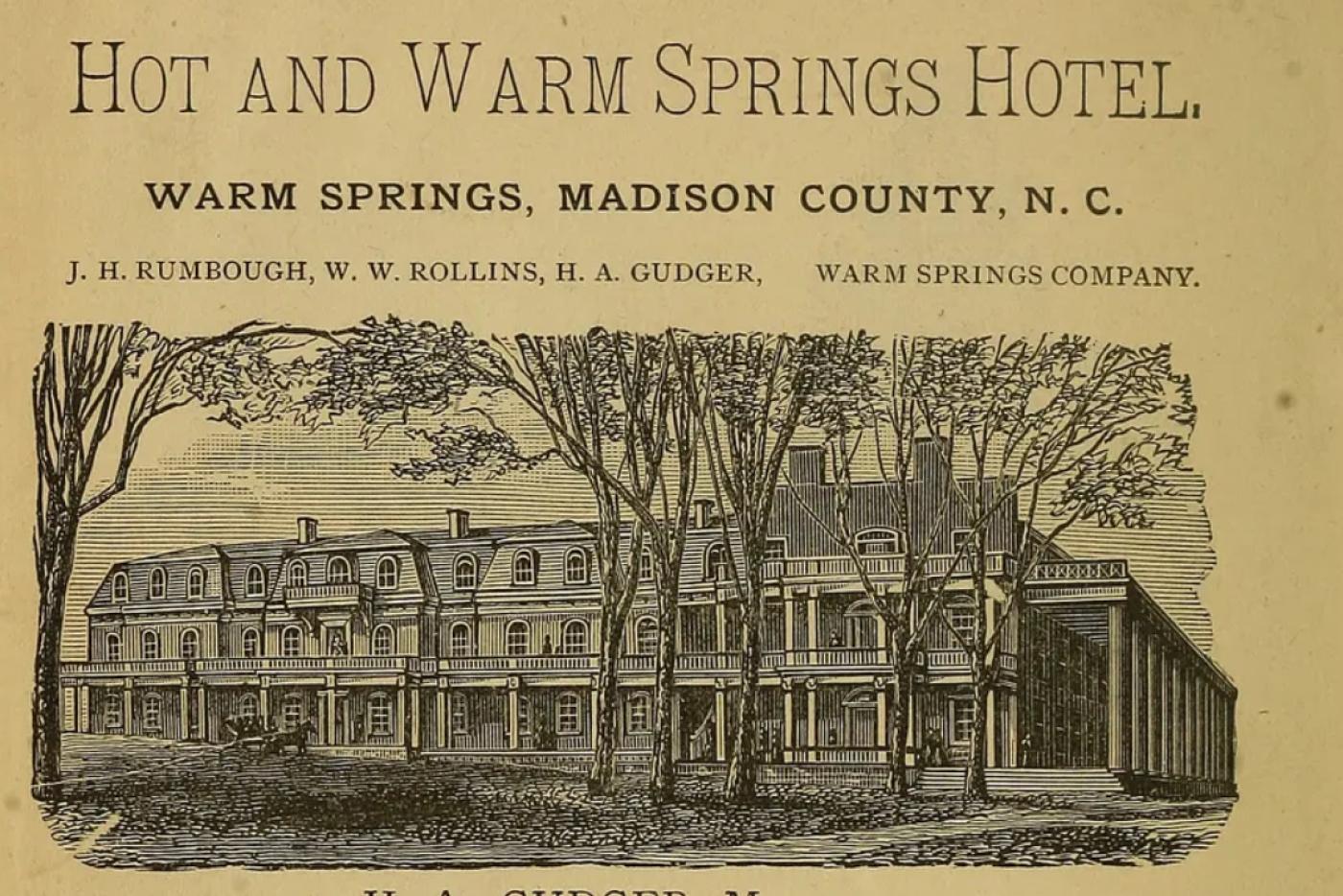

An advertisement for the hotel from 1883, the year before the Patton hotel burned. The thirteen columns can be seen on the right. William Gleason Zeigler and Ben S. Grosscup, In the Heart of the Alleghanies (Raleigh: A. Williams & Co., 1883), 386.

Today we will look at how the town of Hot Springs, NC developed from a roadside tavern to a nationally known resort in the nineteenth century. The Appalachian Mountains have often been viewed as isolated, sealed away, behind the times. Around the turn of the twentieth century, when railroads spread through the mountains and allowed writers from elsewhere to “discover” them, it became fashionable to refer to mountain people as “our contemporary ancestors.”

But, although the mountains have a unique cultural heritage, they were never really cut off from the rest of the country. The French Broad River valley, steep and rocky though it is, steered travel and trade through the middle of Madison County until the rise of the highway system. And for the naturally occurring hot mineral waters of Hot Springs, just above the river’s banks, travelers have been coming to the county for its own sake for as long as and longer than written records let us know.

A roadside tavern amid a thinly settled wilderness became a fashionable retreat for wealthy South Carolinians, and then — with the help of the railroad — a resort known all across the country, before a streak of bad luck let it drift from the nation’s mind, and all in little more than a single century. But Hot Springs never stood still and waited to be passed by, any more than the springs themselves ever stopped flowing.

Neilson’s Tavern: A Wilderness Waypoint

Settlers were already pouring into and over the mountains when the United States won its independence. A melting pot of German and Scots-Irish migrants, many of them first arrived in Delaware or Pennsylvania before moving on up the Shenandoah Valley. The tide parted at the northern end of the Blue Ridge, spreading from there into modern-day Tennessee and the upper Piedmont. Then they began flowing into what is now western North Carolina from both sides, one group picking its way through the coves of the steep eastern face of the Blue Ridge while the other moved up river valleys like the French Broad. There, they built homes, burned out fields among the trees, and began painstakingly lacing the uncooperative landscape with roads.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, there stood an already well-established tavern on the banks of the French Broad River in the northern reaches of then-sprawling Buncombe County. The early Methodist bishop Francis Asbury, on his regular visits to the region, often found lodging and much-needed rest there. Asbury observed the conditions encountered by the settlers then flowing into the mountains from both sides. In the late autumn of 1800, for instance, Asbury

arrived at the Warm Springs, not however, without an ugly accident. After we had… passed about thirty yards beyond the Paint Rock, my roan horse… reeled and fell over, taking the chaise with him ; I was called back, when I beheld the poor beast and the carriage, bottom up, lodged and wedged against a sapling, which alone prevented them both being precipitated into the river. After a pretty heavy lift all was righted again, and we were pleased to find there was little damage done. Our feelings were excited more for others than ourselves. Not far off we saw clothing spread out, part of the loading of household furniture of a wagon which had overset and was thrown into the stream, and bedcloaths [sic], bedding, &c. were so wet that the poor people found it necessary to dry them on the spot. We passed the side fords of French Broad, and came to Mr. Nelson’s [at Warm Springs] …My company was not agreeable here — there were two [sic] many subjects of the two great potentates of this western world — whiskey — brandy. My mind was greatly distressed.[1]

Clearly, “the Warm Springs” (now Hot Springs) were already not only a waypoint but a social gathering place amid the semi-wilderness, even if the bishop did not approve of the gatherings.[2] Just two years later, Asbury found conditions much improved in multiple respects:

We… continued on to the Paint mountain, passing the gap newly made, which makes the road down to Paint-Creek much better : I lodged with Mr. Nelson, who treated me like a minister, a Christian, and a gentleman.[3]

Asbury found travelers gathered at Nelson’s, or Neilson’s, tavern — the previous year, he recorded in his journal having “expounded the Scriptures” to “about thirty travellers [who had] dropped in” at Warm Springs. But their numbers were limited by the difficulty of the roads; the fifty-seven-year-old bishop had had a rough morning scrambling over Paint Mountain: “with the help of a pine sapling, [I] worked my way down the steepest and roughest part… I could bless God for life and limbs.”[4]

The Warm Springs Hotel: The Aristocratic Summer

From 1828, the construction of the Buncombe Turnpike between Greenville, SC and Greeneville, TN galvanized the transformation of “the Warm Springs” from a remote tavern to a nascent resort. Around that time, Neilson sold the site to an Irish-born entrepreneur named James Patton, in whose family it would stay for the rest of the antebellum period.

The new road linked the coastal plain with the Appalachians, from the Blue Ridge west over the “Great Iron Mountains” (now the Great Smokies) to the burgeoning frontier on the Cumberland Plateau. Amid the pines and oaks and towering tulip poplars, sheep grazed the undergrowth and pigs and turkeys feasted on the abundant chestnuts. Once a year, in a great surging migration, the drovers and drivers of the mountains gathered their herds and flocks and drove them south down the turnpike.

Along the road thrived a string of “stands,” roadside inns built to accommodate thousands of livestock along with their drivers. Several stands along the French Broad eventually grew into a town — graced by the puzzling name “Lapland,” shared with the northernmost reaches of Scandinavia — that finally became the county seat and changed its name to Marshall.

Beside this now-pulsing artery of commerce, Patton replaced the old tavern with a vast brick hotel. The supposed medicinal properties of the spring water had attracted a trickle of visitors since the 1780s, but now, with the turnpike and the hotel, the trickle became a flood, and Warm Springs became a favorite summer retreat for the South Carolina elite. One account[5] estimates that by 1833 fully a thousand guests regularly attended the hotel’s nightly balls; another, from the 1840s, caps the hotel’s occupancy as 500 at its summer peak.[6]

The visitor approaching the building for the first time, up its gravel driveway, would have seen it framed by a grove of locust trees, its backdrop one of the more sedate stretches of the French Broad, with the Bald Mountains as a near horizon. It was fronted by a vast portico of thirteen white-stuccoed columns symbolizing the thirteen original colonies. Not far away stood the bathhouse, with its two four-foot-deep pools; huddled around it was a collection of brick buildings with guest rooms for those who (it was thought) needed to be close to the waters for medical reasons. Those accommodations, however, were so startlingly spartan that one visiting writer, a member of Parliament bearing the aggressively British name of James Silk Buckingham, thought that “all the benefit of bathing in the waters must be more than counteracted by the privations and discomfort of the lodgings.”[7]

The main building was more sumptuous; the original brick structure, supplemented with brick additions, gave it a seven-hundred-foot-long front. In the additions could be found the hotel’s “vast, barrack-like dining-room, with a noble ball-room above,” according to the writer Charles Dudley Warner.[8] The 1876 novel The Land of the Sky, by the travel writer Christian Reid (a pseudonym for Frances Christine Fisher), was so popular that its title became a nickname and tourism slogan for western North Carolina as a whole; in it, when Reid’s characters visit Warm Springs, she provides an account of the pastimes to which it played host each summer:

Who does not know the routine? A vast amount of lounging and promenading on piazzas [that is, porches], a considerable amount of flirtation under lawn-trees, much smoking on the part of the men, unlimited gossip on the part of the women, idle hours in the bowling-alley, idle hours by the river pretending to fish, idlest hours of all in the ballroom, criticising faces and costumes, and dancing to poor music.[9]

To describe the social life, Warner adds:

The long colonnade made an admirable promenade and lounging-place and point of observation. It was interesting to see the management of the ferry, the mounting and dismounting of the riding-parties, and to study the colors on the steep hill opposite, halfway up which was a neat cottage and flower-garden. The type of people was very pleasantly Southern. Colonels and politicians stand in groups and tell stories, which are followed by explosions of laughter ; retire occasionally into the saloon, and come forth reminded of more stories, and all lift their hats elaborately and suspend the narratives when a lady goes past.[10]

Warner, a New Englander, took his visit as an opportunity to indulge in some of the mythology of the antebellum South, disregarding its cost: the Pattons’ hotel relied on slave labor from its founding. Buckingham, an opponent of slavery, reported that a ten-year-old girl was sent to clean his room, and that in talking to her he learned that she and her mother had been born in Virginia and sold to the hotel by a slaveholder who was also her father.[11] The hotel also hosted slave auctions during that period. In the 1950s, the Asheville author Wilma Dykeman spoke to a woman who had been born enslaved in Tennessee and told the story of how her mother had arrived in the mountains: she was brought from Mexico (perhaps to elude the ban on the slave trade theoretically in effect since 1808) all the way to Warm Springs, a long shoeless march on bloody, ragged soles.[12]

References:

[1] Francis Asbury, Journal of the Rev. Francis Asbury, Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, from August 7, 1771 to December 7, 1815, v. 2 (New York: N. Bangs and T. Mason, 1821), 400. Emphasis original.

[2] Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Americans consumed staggering quantities of alcohol. The average New Englander drank thirty-five gallons of apple cider a year by the eve of the Revolution. Eric Rutkow, American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation (New York: Scribner, 2012), 57.

[3] Asbury, v. 3, 119.

[4] Ibid, 83.

[5] Bob Hurley, “Hot Spring’s Changing Scene,” Marshall News-Record, October 14, 1971, 2–3.

[6] J. S. Buckingham, The Slave States of America, v. 2 (London: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1842), 210. Perhaps, after the building was gutted by fire in 1838, Patton hat rebuilt for a lower capacity.

[7] Ibid, 200.

[8] Charles Dudley Warner, On Horseback: A Tour in Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1888), 136.

[9] Christian Reid (pseud.), The Land of the Sky: or, Adventures in Mountain By-ways (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1876), 49.

[10] Warner, 137.

[11] Buckingham, v. 2, 213–4.

[12] Wilma Dykeman, The French Broad (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1955), 340. It is worth noting as well that, even after the Civil War, the hotels at Warm/Hot Springs replicated the same racial hierarchy as the rest of the Jim Crow South. The hotel’s staff was still almost entirely black, which obviously played into Warner’s antebellum fantasies. And Hezekiah Gudger’s 1883 advertisement for the hotel, pictured above, casually notes: “Children under 10 years of age and colored servants half price.”