Author: Matthew M. Peek, Military Collection Archivist

![Photograph shows Elise (Elyse) Robert and Dorothy Kohn putting 2nd Liberty Loan posters on the side of the Waldorf Astoria in New York City during World War I. (Source: Flickr Commons project, 2015 and The Washington Times, Oct. 8, 1917) [from Library of Congress, LC-B2- 4351-6].](https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/World-War-I/25395v.jpg) World War I began in Europe in 1914, the same year the U.S. Federal Reserve System was established. Starting in 1917, the U.S. government began a campaign to raise funds from private citizens to finance our involvement in World War I. Wars are expensive. As with every governmental effort, wars have to be financed through a combination of taxation, borrowing, and the expedience of printing money. For this war, the federal government relied on a mix of one-third new taxes, and two-thirds borrowing from the general population. Very little new money was created by the U.S. Treasury Department, which helped to control wartime inflation. The borrowing effort was called the “Liberty Loan,” and was made operational through the sale of Liberty Bonds. These securities were issued by the Treasury, but the Federal Reserve and its member banks conducted the bond sales.

World War I began in Europe in 1914, the same year the U.S. Federal Reserve System was established. Starting in 1917, the U.S. government began a campaign to raise funds from private citizens to finance our involvement in World War I. Wars are expensive. As with every governmental effort, wars have to be financed through a combination of taxation, borrowing, and the expedience of printing money. For this war, the federal government relied on a mix of one-third new taxes, and two-thirds borrowing from the general population. Very little new money was created by the U.S. Treasury Department, which helped to control wartime inflation. The borrowing effort was called the “Liberty Loan,” and was made operational through the sale of Liberty Bonds. These securities were issued by the Treasury, but the Federal Reserve and its member banks conducted the bond sales.

The Liberty Loan campaigns marked the first time that the average American worker or citizen was asked to be an investor by the federal government. The Liberty Loan campaigns relied upon civic organizations, wartime citizen groups, and state governments to promote and collect as authorized Liberty Loan vendors money for the federal government.

The Liberty Loan bonds were negotiable, with coupons cashable every six months. Although their term was thirty years, they were callable by the holder after fifteen years. The lowest denomination available was $50. Some people would put them out of reach for the general public. The average compensation of a production worker in manufacturing in 1917 was approximately 35 cents per hour—$50 would require two weeks of wages. But there was an obstacle to issuing lower denominations: the government did not want to deal with the administrative cost of tracking ownership of the bonds, so it designated Liberty Bonds as “bearer bonds.” These are securities that belong to whoever is holding them at the time rather than one registered owner. Had bearer bonds been issued in small denominations, they could be used like currency to purchase goods--they would function as money.

U.S. Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo found another way to make the bonds affordable to the general public. He introduced an installment plan, in which even the poorest could purchase “War Thrift Stamps” that cost only 25 cents. The Treasury Department called them “little baby bonds,” and like the Liberty Bonds, they earned interest. The stamps were pasted on a card until sixteen had been collected, at which point they were exchanged for a $5 stamp called a “War Savings Stamp.” These were affixed to a “War-Savings Certificate” which also earned interest. When ten $5 stamps were collected, the certificate could be exchanged for a $50 Liberty Bond. The key to this scheme was that the certificate was registered to its owner and could be cashed only by the person whose name was inscribed on the certificate. That made the certificate non-negotiable.

![Ring It Again Second Liberty Loan of 1917 campaign poster [circa October 1917] (MilColl.WWI.Posters.9.48).](https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/World-War-I/Ring_It_Again.jpg)

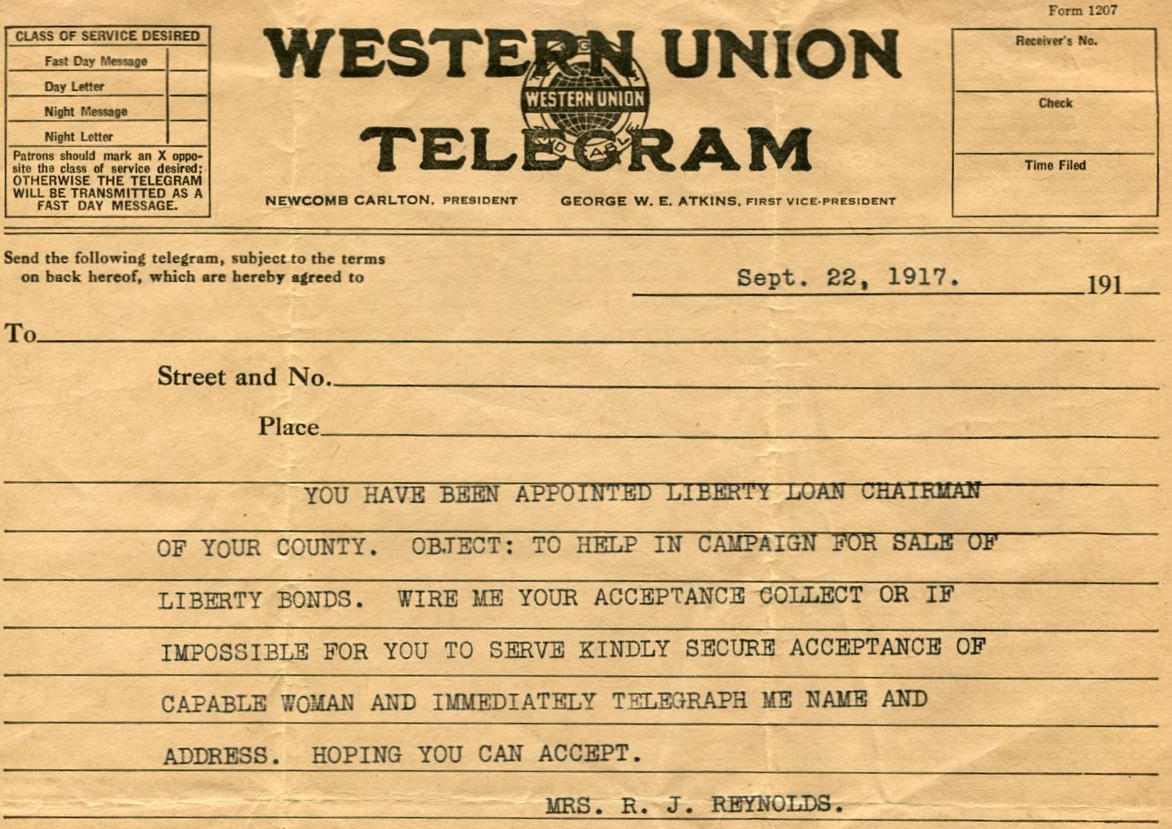

The first Liberty Loan drive in May 1917 used 11,000 billboards and streetcar ads in 3,200 cities to promote the sale of the bonds to the general public. The 2nd Liberty Loan Act, passed by the U.S. Congress to go into operation in October 1917, established a $15 billion aggregate limit on the amount of government bonds issued, allowing $3 billion more offered at 25 years at 4% interest, redeemable after 10 years. The Second Liberty Loan took place October 1 through October 28, 1917. During the second drive, 60,000 women were recruited by the federal government to sell bonds. Out of this rose the volunteer Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, which was a national non-profit organization of women specifically formed to support the loan effort. Each state and county had their own chapters of the committee.

The first Liberty Loan drive in May 1917 used 11,000 billboards and streetcar ads in 3,200 cities to promote the sale of the bonds to the general public. The 2nd Liberty Loan Act, passed by the U.S. Congress to go into operation in October 1917, established a $15 billion aggregate limit on the amount of government bonds issued, allowing $3 billion more offered at 25 years at 4% interest, redeemable after 10 years. The Second Liberty Loan took place October 1 through October 28, 1917. During the second drive, 60,000 women were recruited by the federal government to sell bonds. Out of this rose the volunteer Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, which was a national non-profit organization of women specifically formed to support the loan effort. Each state and county had their own chapters of the committee.

The chairwoman of the North Carolina Women’s Second Liberty Loan Committee was Katharine Smith Reynolds, wife of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company founder R. J. Reynolds. The State of North Carolina would raise 5 million dollars during the October 1917. There would be a total of five Liberty Loan campaigns between May 1917 and April 1919. North Carolina contributed significant amounts of money during all of the drives. Mary G. Shotwell of Kinston, N.C., served during WWI as the educational director for the U.S. Treasury Department, and assisted in developing War Savings Stamp and Liberty Loan campaign materials and lessons for public schools. North Carolina women had a significant impact on the state and country as a result of Liberty Loan campaigns, which also helped to organize

![Lend Your Money To Your Government Second Liberty Loan of 1917 campaign poster.The newness of this concept lending the U.S. government money and how it would be repaid caused confusion among that general population. A clarification of the meaning of “interest paid” was incorporated into this poster for the Second Liberty Loan drive [circa 1917] (MilColl.WWI.Posters.9.46).](https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/World-War-I/Lend_Your_Money_To_Your_Government.jpg)

The resulting propaganda posters that resulted from the Second Liberty Loan campaign—as well as all subsequent Liberty Loan campaigns—have become some of the most recognized visual pieces from WWI. The colors of, slogans of, and patriotism advertised on the poster captured the country’s attention, and were posted everywhere in America. In North Carolina, Liberty Loan drive posters were put up in factories and businesses, schools, public places, banks, stores, and numerous other locations. Schools ran Uncle Sam War Savings Stamp Societies throughout North Carolina.

To see and download digitized Liberty Loan campaign posters, check out the State Archives of North Carolina’s WWI Posters Collection on the North Carolina Digital Collection.

![Handmade poster display for a war savings stamp drive during WWI by schoolchildren of the Uncle Sam War Savings Stamps Society at Murphey School, Raleigh Public Schools [undated] (From Mary G. Shotwell Collection, Liberty Loan Campaigns, WWI Papers).](https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/World-War-I/M.G.ShotwellColl.LibertyLoan.WWI%20Papers.jpg)

You can also check out the Liberty Loan Campaigns Records and Mary G. Shotwell Collection in the WWI Papers of the Military Collection at the State Archives of North Carolina.

Sources

The Second Liberty Loan of 1917: a source book, United States Department of the Treasury Publicity Bureau, 1917.

Report of National Women's Liberty Loan Committee for the First and Second Liberty Loan Campaigns, 1917.

Richard Sutch, "Liberty Bonds, April 1917–September 1918," published on Federal History Reserve, December 2015, viewed at https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/liberty_bonds#footnote1 (a majority of the first half of this blog post is taken directly from or adapted from this piece).